Hank

Williams

-

Inducted1961

-

Born

September 17, 1923

-

Died

January 1, 1953

-

Birthplace

Mount Olive, Alabama

Almost singlehandedly, Hank Williams set the agenda for contemporary country songcraft, but his appeal rests as much in the myth that even now surrounds his short life. His is the standard by which success is measured in country music on every level, even self-destruction.

Rural Origins

Williams’s legend now overshadows the rather frail and painfully introverted man who spawned it. Born Hiram Williams, the “Hillbilly Shakespeare” came from a rural background. His parents were probably strawberry farmers when he was born, although his father, Lon, later worked for logging companies around Georgiana in south Alabama.

Williams was born with a spinal deformity, spina bifida occulta, that would later have a harmful impact upon his life. Lon, a World War I veteran, entered a Veterans Administration hospital in 1930 when Hank was six, and his son rarely saw him until the early 1940s. Hank’s mother, Lillie, moved the family to Greenville and then, in 1937, to Montgomery, Alabama.

Williams’s musical career was already underway by the mid-1930s, and he formed the first of his Drifting Cowboys bands around 1938. He spent the war years shuttling between Montgomery, where he played music, and Mobile, where he worked in the shipyards. In December 1944, he married Audrey Mae Sheppard, and, after the war, he reformed the Drifting Cowboys and became the biggest hillbilly music star in Montgomery. His progress was impeded, though, by his drinking, which was already problematic, and by the fact that his music was considered anachronistic.

Songs

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

Rise to Stardom

Nashville music publisher Fred Rose nonetheless invited Williams to supply songs for Molly O’Day, and that contact led to Rose offering him the chance to record for Sterling Records in December 1946. Based on the public response to those records, Rose was able to place Williams with MGM Records, and his first MGM release, “Move It on Over,” was a hit in the fall of 1947.

Eventually, Rose secured Williams a regular spot on a relatively new radio jamboree, the Louisiana Hayride, in Shreveport. Williams moved there in August 1948 and began performing “Lovesick Blues,” a pop song dating back to 1922 that he had learned from a recording by either Rex Griffin or Emmett Miller. The response it received encouraged Williams to record it after the 1948 recording ban ended. It reached #1 in May 1949 and stayed there sixteen weeks. The success of “Lovesick Blues” and its follow-up, another nonoriginal called “Wedding Bells,” convinced the Grand Ole Opry to hire Williams, despite misgivings about his reliability.

Williams moved to Nashville in June 1949 and swiftly became one of the biggest stars in country music. Increasingly, he decided to stand or fall with his own songs, and, after the success of his own “Long Gone Lonesome Blues” in the spring of 1950, virtually all his hits were his own compositions.

At the session that produced “Long Gone Lonesome Blues,” Williams began to record a series of narrations and talking blues to be issued under the pseudonym “Luke the Drifter.” Most of them had a strong moral undertone, making them unsuitable for the jukebox trade, which accounted for more than half of his record sales. MGM Records never made any serious attempts to hide the identity of Luke the Drifter; it was simply a ploy to avoid jukebox distributors ordering unsuitable records.

The peak years of Williams’s career were 1950 and 1951. He was one of the most successful touring acts in country music. Every one of his records charted, except for those issued as Luke the Drifter and his religious duets with Audrey. His songs, which had matured greatly since the demos he had submitted to Molly O’Day, began finding a wider market than his own recordings of them ever could. Starting with “Honky Tonkin’” in 1949, his songs had been covered for the pop market, but it was not until Tony Bennett covered “Cold, Cold Heart” in 1951 that he began to be recognized as an important popular songwriter. From that point, a rush was on to reinterpret his songs for the pop market. Guy Mitchell, for instance, had a hit with “I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still in Love with You),” and the duo of Frankie Laine and Jo Stafford took “Hey, Good Lookin’” into the pop Top Ten.

Videos

“Hey, Good Lookin’” with the Drifting Cowboys

The Kate Smith Evening Hour, 1952

The peak years of Hank Williams’s career were 1950 and 1951. He was one of the most successful touring acts in country music.

Photos

-

Studio portrait of Hank Williams, c. 1949. Photo by Walden S. Fabry Studios.

-

Publicity photo of Audrey Williams and Hank Williams singing into WSM microphone, c. 1951. Photo by Henry Schofield.

-

Hank Williams (standing, second from right) and the Drifting Cowboys at radio station WSFA, in Montgomery, Alabama, 1945. Audrey Williams is at far right.

-

Hank and Hezzy's Driftin' Cowboys, c. 1938. Williams is second from left.

-

Hank Williams (third from right) and the Drifting Cowboys, displaying the products of their radio sponsor, Mother’s Best Flour Company, 1951.

-

Studio portrait of Hank Williams and the Drifting Cowboys, c. 1951. Back row (from left): Cedric Rainwater, Hank Williams, Don Helms. Front row (from left): Jerry Rivers, Sammy Pruett.

-

Hank Williams (third from left) at MGM Variety Record Shop event in Louisville, Kentucky, 1950.

-

Hank Williams (in light-colored suit at center) and the Drifting Cowboys in WSM Studio C during the “Duck Head Saturday Night” radio show, 1949.

-

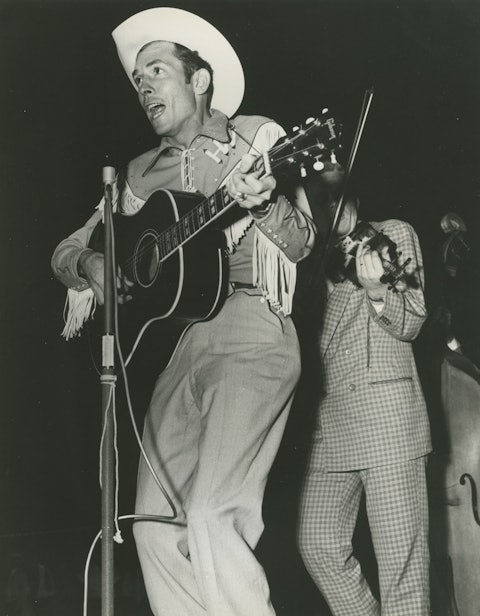

Hank Williams onstage as part of the Hadacol Caravan, in Columbus, Ohio, 1951.

-

Hank Williams Sr. and Hank Williams Jr. at home, 1950.

Struggles with Alcohol and Painkillers

Williams had long wrestled with his alcoholism, but career pressures, marital problems, and crippling spinal pain all contributed to make his drinking binges more frequent during 1951. In December, he underwent surgery on his back, but the operation was not a success and led to a dependence on painkillers. Meanwhile, he disbanded his group, and when he started work again in March and April 1952, it was with pickup bands. Audrey had ordered him out of the family home immediately after he came home from the hospital, and he moved into a house with Ray Price.

As 1952 wore on, Williams appeared to care less and less about his career. His appearances were few, and by June, he had stopped working altogether. In August, he was fired by the Grand Ole Opry and moved back to Montgomery. Fred Rose negotiated his return to the Louisiana Hayride as of September, and Williams moved back to Shreveport that month. In October, he married Billie Jean Jones Eshliman. She was from Bossier City, near Shreveport, but he had met her in Nashville when she came there with Faron Young. By this point, another girlfriend, Bobbie Jett, was pregnant with Williams’s child.

Williams worked in Shreveport from September to December 1952. Most of his bookings were in beer halls, and his drunkenness was now a serious problem, which was compounded by medication prescribed by a bogus doctor, Toby Marshall. Through it all, though, Williams never seemed to strike out in the studio. Even as he played small halls in East Texas, his recording of “Jambalaya” was #1. If anything, his hits increased in magnitude as his bookings diminished.

Just before Christmas 1952 Williams took a leave of absence from the Hayride and returned to Montgomery to rest. On December 30, he left for a booking in Charleston, West Virginia, followed by another in Canton, Ohio, but died en route. He may have died on December 31, 1952, in the back seat of his chauffeured Cadillac, but he was not pronounced dead until early on January 1, 1953, in Oak Hill, West Virginia.

—Colin Escott

Adapted from the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum’s Encyclopedia of Country Music, published by Oxford University Press