Chapter 1

City Sounds

Origins of Nashville R&B

The Fairfield Four, c. 1947. Bottom row, from left: Sam McCrary, James S. Hill, and George Gracie. Top row, from left: Rufus Carrethers, Willie Frank Lewis, and Rev. Edward “Preacher” Thomas. Courtesy of Jerry Zolten.

The term “rhythm & blues,” or “R&B,” came into common usage in the late 1940s to describe a form of Black popular music that evolved primarily from prewar jazz, blues, and gospel. In segregated Nashville, jazz and blues flourished in Black nightclubs and theaters, while the gospel influence took hold in churches. Many who played the music learned their craft in the rigorous education programs of the city’s Black high schools and colleges.

Black Entertainment Districts

Reflecting years of urban migration, enforced segregation, and general demographic shifts, much of Nashville’s Black entertainment centered on two streets: Fourth Avenue North and Jefferson Street. Both districts housed numerous theaters, nightclubs, eateries, and Black-oriented businesses.

Bijou Theater

In 1916, after a three-year dormancy, the Bijou Theater on Fourth Avenue North reopened as a Black-oriented venue. As part of the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA) circuit during the 1920s and 1930s, the white-owned Bijou brought in legendary Black performers such as blues singer Bessie Smith. Nashville jazz great Adolphus “Doc” Cheatham played in the Bijou’s orchestra pit as a teenager, and for many years local impresario Jerrie Jackson hosted a vaudeville-style program at the Bijou, through which many of the city’s Black entertainers passed.

Jerrie Jackson, c. 1940s. Courtesy of Tempest Utley.

Jerrie Jackson, c. 1940s. Courtesy of Tempest Utley.

This view of the Bijou Theater appeared on a 1908 postcard. Courtesy of the Nashville Public Library’s Nashville Room.

"I couldn't work for the whites, you understand that, so the only way I could get any experience was sitting in the [Bijou] pit with the band and playing the shows . . . because I wanted to learn more about singers, blues singers and all that."

- Doc Cheatham, Jazz Musician

Bijou Chorus Line

Regular performers at the Bijou, the chorus-line dancers with Jerrie Jackson’s Hep Cats included Jackson’s wife, Irene, and his daughter Geraldine.

"Looking back on it, I think [the Bijou] did a lot for, I'll say the Black community. It gave them something of their own to see, and enjoy. And that's what they did. And they really supported it. They really did."

- Irene Jackson, Bijou Dancer

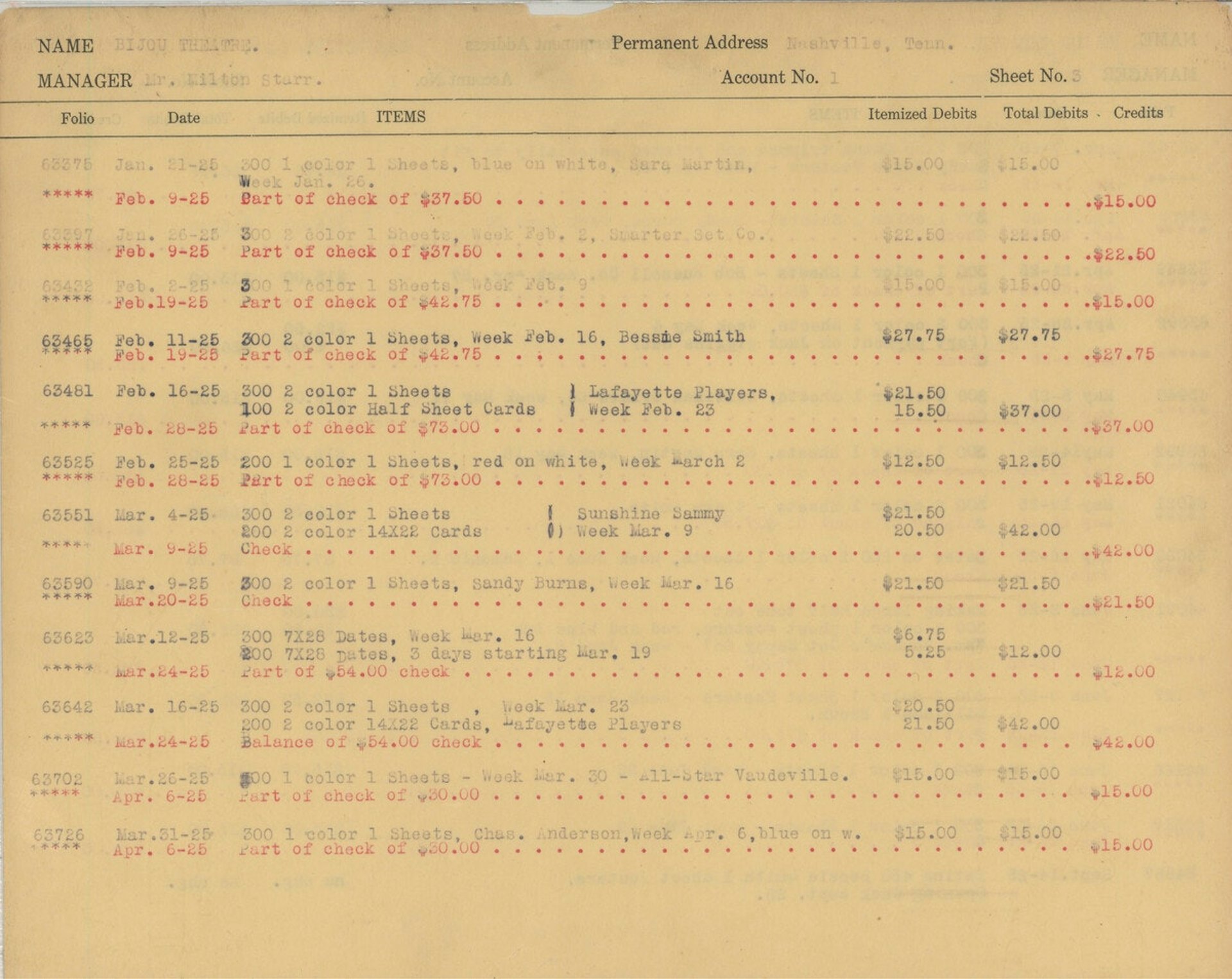

This Hatch Show Print ledger sheet is from the Nashville poster shop's Bijou Theater account. Note the February 11, 1925, order for three hundred Bessie Smith posters.

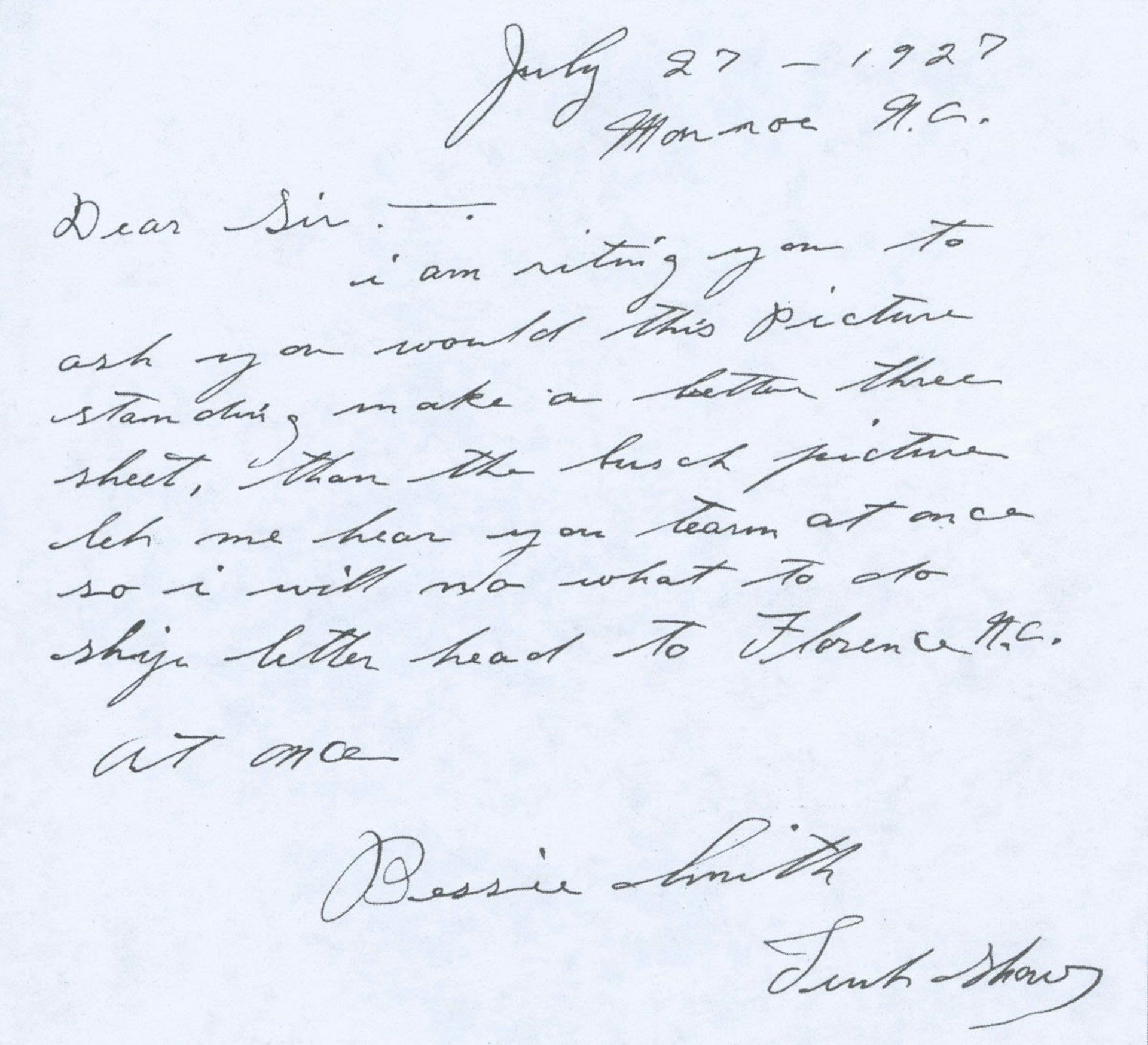

Bessie Smith sent this handwritten letter and photo to Hatch Show Print in 1927.

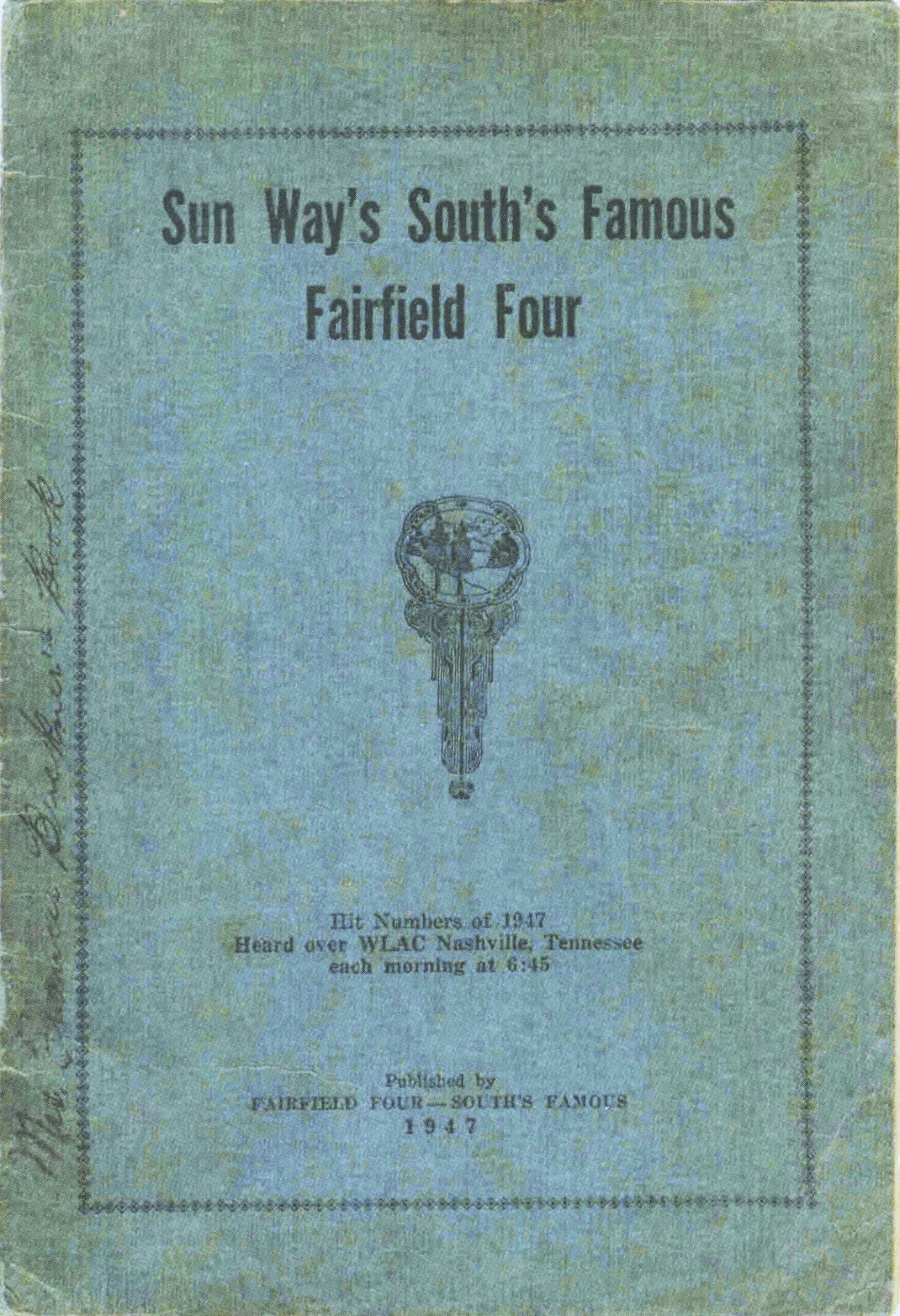

Gospel

Though frequently risqué lyrics and the nightclub lifestyle made R&B objectionable to many gospel music listeners, R&B singers drew much from the vocal techniques of gospel groups, and in many instances, emerged from their ranks. Renowned within that gospel tradition, Nashville’s Fairfield Four became nationally prominent when the CBS network picked up their 1940s radio broadcasts for local station WLAC.

The Fairfield Four, c. 1947. Bottom row, from left: Sam McCrary, James S. Hill, and George Gracie. Top row, from left: Rufus Carrethers, Willie Frank Lewis, and Rev. Edward “Preacher” Thomas. Courtesy of Jerry Zolten.

This 1947 publication contains the lyrics to songs such as the Fairfield Four's signature gospel anthem, "Don't Let Nobody Turn You Round." Courtesy of Jerry Zolten.

Jazz

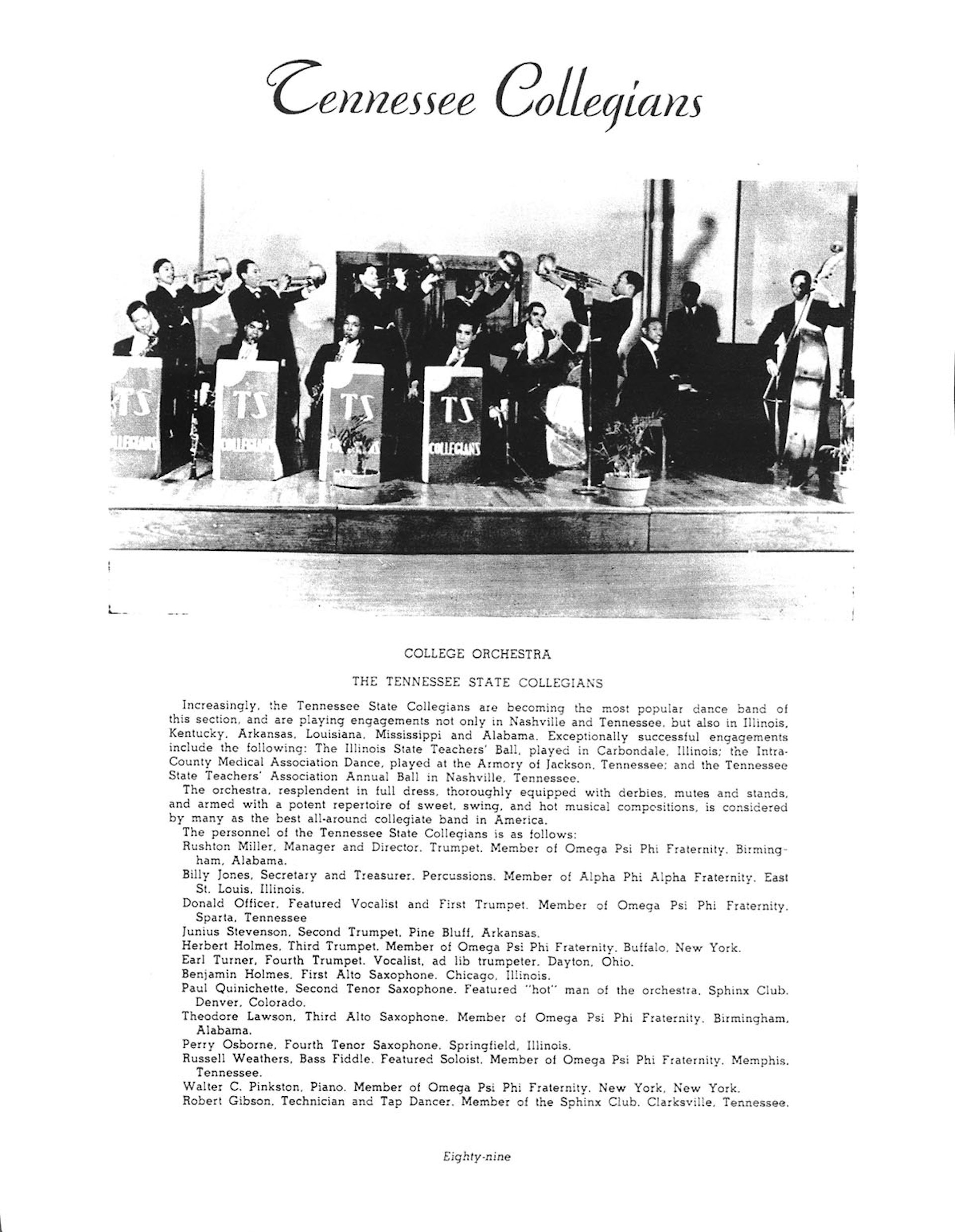

Known until 1968 as Tennessee A&I, the historically Black Tennessee State University in Nashville prided itself on having one of the top jazz education programs in the country. Longtime band director Jordan “Chick” Chavis recruited heavily in Memphis and elsewhere for the school’s Tennessee State Collegians jazz ensemble. In 1949, readers of the influential Black newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier voted the Collegians the nation’s top college dance band. In recognition of the honor, they were invited to perform at Carnegie Hall.

This original Carnegie Hall program is from the 1949 concert at which the Tennessee State Collegians performed. Courtesy of Carnegie Hall.

This original Carnegie Hall program is from the 1949 concert at which the Tennessee State Collegians performed. Courtesy of Carnegie Hall.

Tennessee State Collegians

Various members of the Tennessee State Collegians jazz band seen here (c. 1947-48) were also active in Nashville R&B. Two months after the Collegians’ 1949 performance at Carnegie Hall, a tragic tour bus accident took the lives of drummer Paul Kidd and business manager James Welch (not pictured).

Front row, from left: Eugene Carruthers (vocals); John Armstead, John Reed, Andy Goodrich, Samuel Ford, George Hunter (saxophones); and Estil “Glen” Covington (vocals). Second row, from left: Theophilus Griffin (standing, saxophone); Prince Shell (vibraphone); Walter Brown, Willie Weaver, Thomas Woods, Thomas Brooks (trombones); Nelson Jackson (piano); and Jordan “Chick” Chavis (standing, leader). Third row, from left: Henry Thompson, Floyd Jones, Earle “Sonny” Turner, James “Doc” Kendricks (trumpets); and Clifford McCray (bass). Back: Paul Kidd (drums). Courtesy of Tennessee State University’s Special Collections Unit.

Spin the Record