Merle

Haggard

-

Inducted1994

-

Born

April 6, 1937

-

Died

April 6, 2016

-

Birthplace

Bakersfield, California

Merle Haggard stands, with the arguable exception of Hank Williams, as the single most influential singer-songwriter in country music history. He was one of country music’s most versatile artists, stylistically mining honky-tonk, blues, jazz, pop, and folk. Haggard’s repertory ranged wide: aching ballads (“Silver Wings”), sly, frisky narratives (“It’s Been a Great Afternoon”), semi-autobiographical reflections (“Mama Tried”), political commentaries (“Rainbow Stew”), proletarian homages (“Workin’ Man Blues”), and drinking songs that are jukebox, cover-band, and closing-time standards (“I Think I’ll Just Stay Here and Drink”).

Haggard’s acolytes are legion and include many of country music’s brightest and lesser lights, as well as thousands of nightclub musicians. As fiddler Jimmy Belken, a longtime member of Haggard’s exemplary touring band, the Strangers, once told the New Yorker, “If someone out there workin’ music doesn’t bow deep to Merle, don’t trust him about much anything else.”

Bakersfield Beginnings

Merle Ronald Haggard was born poor, though not desperately so, in Depression-era Bakersfield, California, to Jim and Flossie Haggard, migrants from Oklahoma. Jim, a railroad carpenter, died of a stroke in 1946, forcing Flossie to find work as a bookkeeper.

Flossie was a fundamentalist Christian and a stern, somewhat overprotective mother. Not surprisingly, her youngest child grew quickly from rambunctious to rake-hell. By his twenty-first birthday, Haggard had run away from home regularly, been placed in two separate reform schools (from which he escaped a half-dozen times), worked as a laborer, played guitar and sung informally, begun a family, and performed sporadically at Southern California clubs and, for three weeks, on the Smilin’ Jack Tyree Radio Show in Springfield, Missouri. He’d also spent time in local jails for theft and bad checks.

Haggard’s woebegone criminal career culminated in 1957 when, drunk and confused, he was caught burglarizing a Bakersfield roadhouse. After an attempted escape from the county jail, he was sent to San Quentin, where, in a final burst of antisocial activity, he got drunk on prison home brew, landing himself briefly in solitary confinement.

Haggard was paroled in 1960 and, after a fitful series of odd jobs, got a regular gig playing bass for Wynn Stewart in Las Vegas. Years later, his friend, the iconic songwriter Kris Kristofferson, called Haggard “the most successfully rehabilitated prisoner in American history.”

Songs

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

Getting His Start

Another Bakersfield mainstay, Fuzzy Owen, signed Haggard to his tiny Tally Records in 1962. After recording five singles there—the first release, “Skid Row” and “Singin’ My Heart Out,” sold few copies; the fourth, “(My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers,” entered Billboard’s Top Ten in 1965—Haggard signed with Capitol.

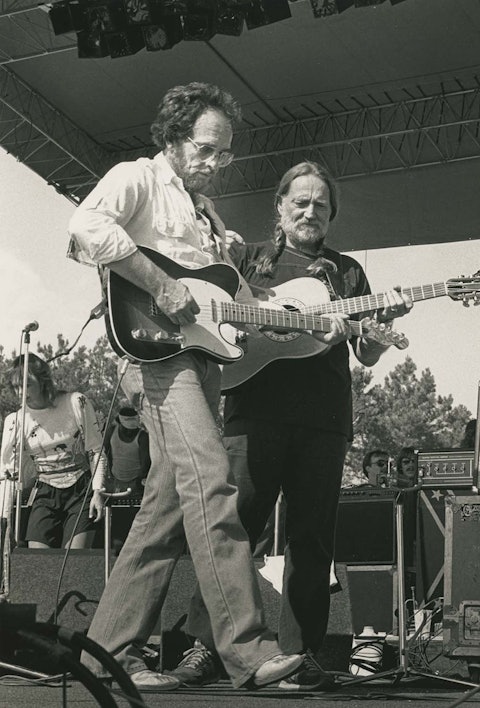

Haggard released his first album, Strangers, in 1965. Roughly seventy feature albums followed, but counting repackagings, reissues, compilations, promotional and movie-soundtrack albums, and albums in which Haggard has participated—with the likes of Ray Charles, Clint Eastwood, Dean Martin, Willie Nelson, Johnny Paycheck, Porter Wagoner, and Bob Wills—Haggard’s number of albums is likely more in the vicinity of 150.

Haggard was also an accomplished instrumentalist, playing a commendable fiddle and a to-be-reckoned-with lead guitar. He and the Strangers played for Richard Nixon at the White House in 1973, at a barbecue on the Reagan ranch in 1982, at Washington’s Kennedy Center, and 60,000 miles from Earth, courtesy of astronaut Charles Duke, who brought a tape aboard Apollo 16 in 1972.

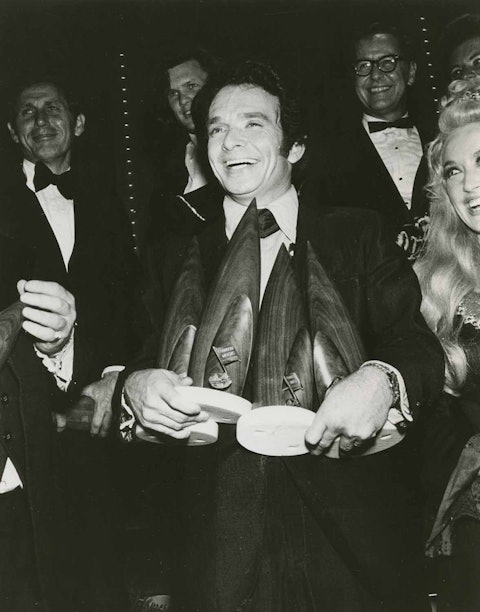

Haggard won numerous Academy of Country Music and Country Music Association awards—including Entertainer of the Year from both organizations in 1970—and was nominated for scores more; was elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1977; and joined the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1994. In 1984, he won a Grammy in the Best Country Vocal Performance, Male category, for “That’s the Way Love Goes.” Even so, he remained famously independent (he once walked out on an imminent appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show) and kept himself at arm’s length from musical Nashville’s sociopolitical vortex.

There was no such thing as a typical Merle Haggard concert. He prided himself on riding the winds of whim and cussedness and, on any given night, might divert from chart and fan favorites and give himself over to a long set of songs by Lefty Frizzell, Jimmie Rodgers, or Bob Wills, the three men who constituted Haggard’s most lasting musical influences.

Additionally, Haggard took great pride in the Strangers’ musicianship, and their importance transcended that of mere sidemen. The band ranged in number from three to ten over the years; incorporated such atypical country instruments as trombones, trumpets, and saxophones; and included long-respected players such as Biff Adam, Norm Hamlet, Roy Nichols, and Clint Strong. The Strangers themselves garnered eight ACM Touring Band of the Year awards.

Videos

“Sing Me Back Home” with Johnny Cash

The Johnny Cash Show, 1969

“The Fightin’ Side of Me” with the Strangers

Donahue, 1982

Merle Haggard was one of country music’s most versatile artists. Stylistically, he mined honky-tonk, blues, jazz, pop, and folk, and his repertory ranged wide.

Photos

-

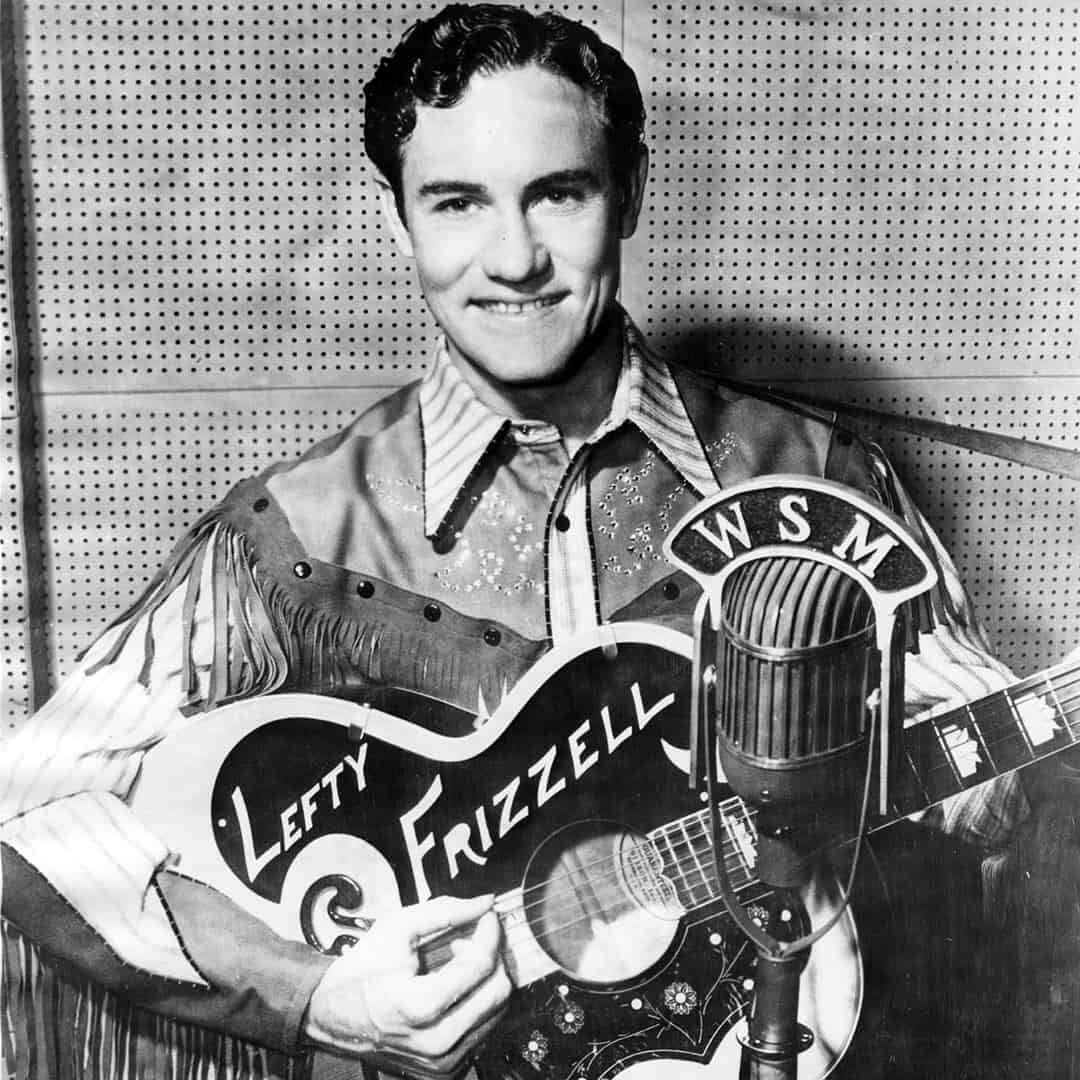

Merle Haggard at the Country Music Association Awards, 1970. That year, he won the Entertainer, Album, Male Vocalist, and Single of the Year categories.

-

Merle Haggard signs autographs at the tenth International Festival of Country Music in London, England, 1983. Photo by Alan Messer.

-

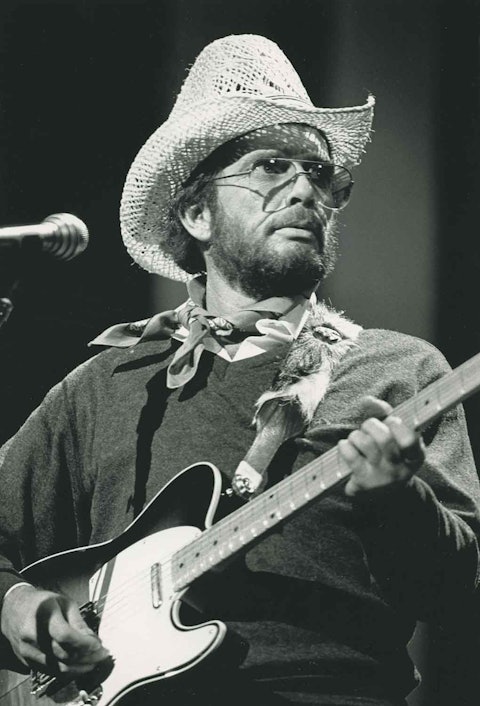

Merle Haggard performs at the Country Music Association Awards, 1983.

-

Merle Haggard and Willie Nelson onstage, 1987.

-

Merle Haggard; his then-wife, Bonnie Owens; and his band, the Strangers, 1968.

-

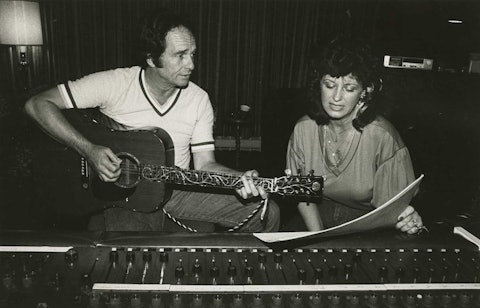

Merle Haggard in the studio with his then-wife, Leona Williams, 1983. Photo by Neil Pond.

-

Merle Haggard and George Jones, 1982. Photo by Alan Messer.

-

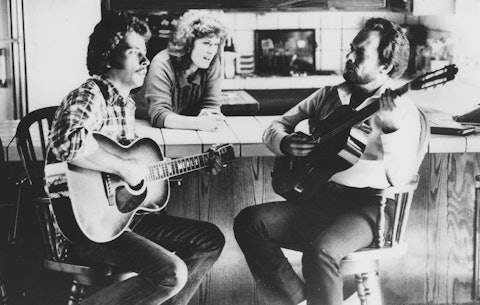

From left: Marty Haggard, Merle Haggard’s son; Leona Williams, Merle Haggard’s then-wife; and Merle Haggard, 1980.

-

Merle Haggard performs at All for the Hall, 2012. Photo by Donn Jones.

-

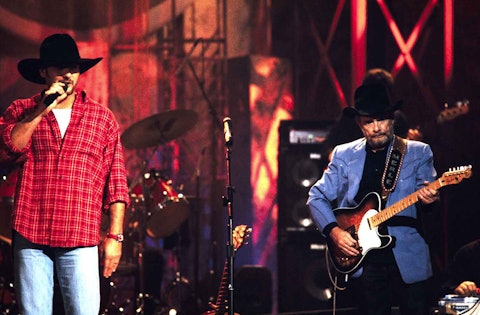

Merle Haggard performs with Tim McGraw during a tribute concert in Haggard’s honor, 1997. Photo by Raeanne Rubenstein.

A Misunderstood Hit

Ironically, Haggard was inextricably linked with a casual ditty that shifted attention from his soaring musicianship to his politics. “Okie from Muskogee” (Capitol, 1969), a #1 song for four weeks and both the ACM’s and CMA’s 1970 Single of the Year, was a seemingly belligerent and defensive screed of traditional American heartland values that appeared at the height of the fractious decade of the Vietnam War.

Haggard’s retellings of the song’s intent were manifold and contradictory. In 1974, he told a Michigan newspaper reporter, “Son, the only place I don’t smoke is Muskogee.” A dozen years later, however, he told the Birmingham Post-Herald that “Okie” was “a patriotic song that went to the top of the charts at a time when patriotism wasn’t really that popular.” Although Haggard frequently bemoaned the public’s perception of him as a political animal, he followed “Okie” with the truly angry “The Fightin’ Side of Me” (Capitol, 1970) and, in 1988, a sentimental reaction to flag burning, “Me and Crippled Soldiers.”

Haggard’s personal life was not without drama. His business acumen was notoriously erratic, and he was married five times. He had six children: four by his first wife, Leona Hobbs, and two by his fifth wife, Theresa Lane. From 1965 to 1978 Haggard was married to singer Bonnie Owens, with whom he recorded a duet album, Just Between the Two of Us (Capitol, 1966), and who was a regular member of Haggard’s musical company. He was also married for a time to singer Leona Williams, who wrote Haggard’s #1 hit “You Take Me for Granted” and co-wrote with Haggard another of his #1 songs, “Someday When Things are Good.”

In 2000, Haggard inspired a flurry of media attention when he aligned himself with Los Angeles-based punk label Epitaph Records to release If I Could Only Fly on its Anti- imprint. On his second release for Anti-, 2001’s Roots Volume 1, Haggard worked with guitarist Norm Stephens, who played on Frizzell’s early recordings.

Haggard kept recording well past retirement age, issuing a tribute to early country recordings, The Peer Sessions, in 2002 and one to acoustic mountain music, The Bluegrass Sessions, in 2007. He won a Grammy for 2007’s Last of the Breed, a collaboration with Willie Nelson and Ray Price, and released a duet album with Nelson, Django & Jimmie, in 2015.

Although he was in and out of the hospital in his later years with heart and respiratory issues, Haggard kept touring until his death from pneumonia on his 79th birthday, April 6, 2016.

—Bryan Di Salvatore

Adapted from the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum’s Encyclopedia of Country Music, published by Oxford University Press